By Allyson Chiu

November 30, 2025

PETALUMA, Calif. — The cows had to be deterred from messing with the experiment.

Researchers from a Bay Area technology company had come to the sprawling dairy farm north of San Francisco to test an emerging solution to planet-warming emissions: microscopic pink organisms that eat methane, a potent greenhouse gas.

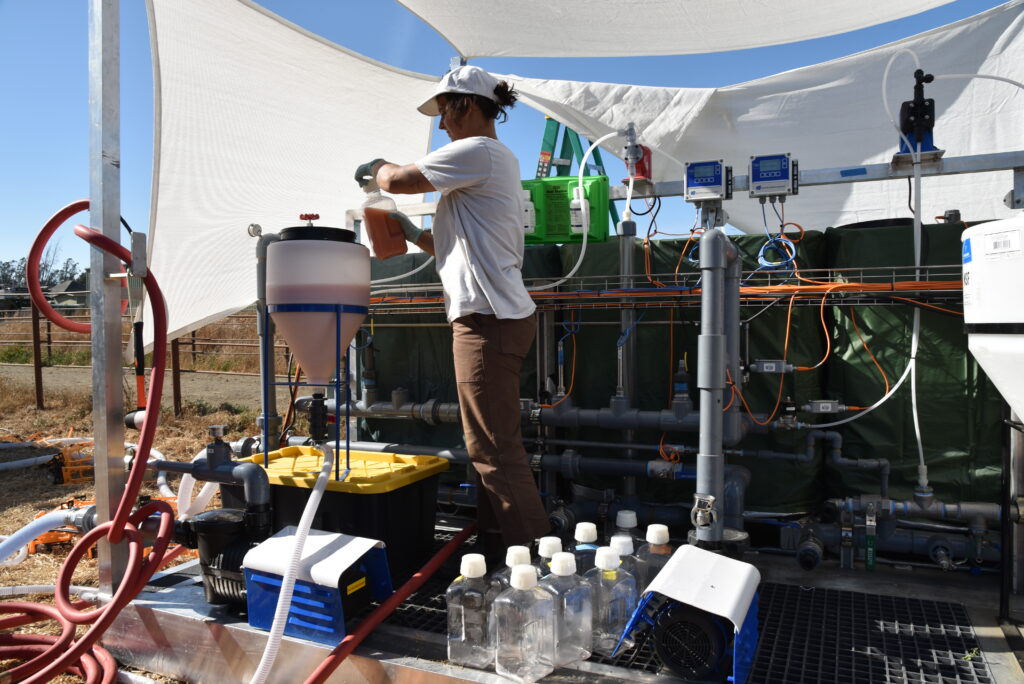

Kenny Correia, 35, of Correia Family Dairy, watched the team from Windfall Bio working near the lagoons used to store manure from the farm’s several hundred cows. The researchers erected a futuristic system of vats, pipes, tubes and shiny metal supports. Then, when everything was assembled, they poured pink liquid into one of the vats. “They were looking like mad scientists out there,” Correia recounted.

He acknowledged initially thinking it was a “crazy idea” to integrate an outdoor laboratory into a working farm. There was the potential for the cows to “be all over it — licking it, pulling out wires and scratching on it,” he said. But livestock farms are a significant source of methane emissions, and Windfall

wanted to see how much the microbes could help.

Fencing around the research equipment kept the cows out. And in June, Windfall reported that the roughly month-long trial had been a success. The microbes had absorbed more than 85 percent of the methane coming from one of the lagoons. “They know how to eat methane,” said Josh Silverman, the company’s CEO and founder. “We’re not creating something new. We’re not teaching them to do

something they don’t normally do. They’ve evolved for a million years to do this.”

Other varieties of microbes — including the tiny organisms in the gut of cows — are among the factors implicated in the increase of methane in the atmosphere, which is warming the Earth.

The gas spews from livestock farms, landfills, wastewater treatment plants, natural gas operations, oil production, rice paddies, wetlands, thawing permafrost and even termite mounds. Although methane breaks down faster than carbon dioxide, its heat-trapping potential is 80 times as powerful in the

first 20 years after it’s released.

Methane-eating microbes could help disrupt that process.

They may be especially useful if deployed at the many scattered sites responsible for small methane emissions, which can collectively add up to a big problem in the atmosphere.

Windfall estimates that if its microbe technology were scaled across the energy, waste and agriculture industries in the United States, it could annually slash up to 1.6 gigatons of carbon dioxide equivalent, an amount produced by driving more than 370 million gas-powered cars for one year.

Another research team, at the University of Washington, says its microbes deployed broadly could capture about 420 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent per year, or what could be generated from driving nearly 98 million gas-powered cars for a year.

To develop a further benefit — and to help make their enterprises more commercially viable — the researchers are working to turn the methane-eating microbes into products such as fertilizer and animal feed, supporting a more sustainable food chain.

“This waste methane is a huge resource,” said Mary Lidstrom, a chemical engineer and microbiologist who is leading the UW project. “Many of the technologies that address the climate really are only addressing climate, but this has a dual outcome.”

*Photo courtesy of Windfall Bio*